Reflection as Evaluation

For museum program facilitators, a post-program reflection tool is a great way to not only reflect on your teaching and facilitation practice, but also generate rich data with which to evaluate your participants’ progress. At Kera, we often include these first-person perspectives in program evaluation designs as an additional data set to triangulate with data representing other relevant perspectives, like those of program participants or museum program managers.

Anyone who plays a role in facilitating and/or teaching the program (or event, tour, etc.) could use these tools—ideally within 24 hours of the program, to ensure your memory of the event is fresh (though often a good night’s sleep can help the reflection process!).

Your reflection tool can be digital or physical, whichever is most convenient and accessible for you. Either way, we have some recommendations for elements to include and questions to ask to ensure that your reflective writing captures important logistical information, appropriate indicators, and considers implications for your future practice.

1..Program Logistics and Participant Characteristics

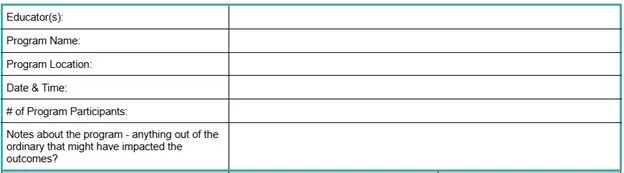

At the top, include any logistical information about the program that will help you analyze the data, like the program date and time. Note that this may not be the same information for every program. For example, if you’re evaluating a school tour program, you might want to record their school and class information; this may be less relevant for a drop-in family program.

This is an example of the top portion for a tool meant to accommodate lots of different programs in the same department with similar outcomes. Here they included logistical details like location in order to distinguish their various programs.

It’s also a space where you can add notes about the group that could affect participant outcomes. Did the group arrive late? Was it larger or smaller than you expected? Was there an event or disruption at the museum that day that might have impacted peoples’ ability to participate?

2. Outcome(s) (What are you evaluating)

It’s also helpful to include a reminder of what specific participant outcomes you’re reflecting on. Outcomes usually require some strategic conversations with those involved with the program and consensus building to articulate a shared idea of what the program’s goals and long term impact are.

This is a reflection tool for a community-centered school partnership program. Program facilitators could rate how much they agree with the statements (which correspond with student outcomes from the logic model), and provide reflective notes underneath.

For example, the outcomes shown above were generated after several conversations with program staff, facilitators, and partners—these informed the creation of a program logic model, which in turn influenced the specific learning goals that program facilitators can focus on in their reflections.

3. Indicator(s) (What you’re looking for)

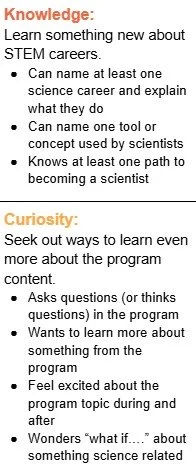

It’s hard to reflect on outcomes without identifying specific participant behaviors, ideas, and actions that indicate growth in specific outcomes. Indicators provide evidence in the form of what participants say , their actions, and other concrete examples of participant engagement that support the program’s outcomes. You may have a sense that participants were working well with each other; however indicators require you to provide the evidence to demonstrate, “how do you know?”

These are examples of two groups of indicators from a post-program reflection tool to measure interest in STEM careers.

4. Reflections on Your Role as Facilitator

We also recommend spending time adding your notes on what you did as the facilitator to support these indicators. Did you choose relevant, engaging objects to discuss? Did you ask questions that pushed participants to think critically about a new idea? Did you encourage active discussion through grouping participants in dynamic ways? Try to be as specific as possible when describing things you said or did or decided that you think might have impacted participant indicators.

These reflections will provide important data to help you understand what participants respond to most. For example, you might notice participants are more actively engaged when working in small groups, or when you use a touch object, or when discussing a particular artist, etc.

5. Space for Notes

Don’t forget to include ample space to take notes or even sketch if that’s more natural for you. Your notes space should be big enough to include your reflections about participant indicators, and ideas about how you supported them. (This is less of an issue if you’re taking notes digitally, of course.)

This is taken from notes on a middle school civics program.

6. Optional Quantitative Scale

Sometimes it’s helpful to have some quantitative data that rates the strength of the indicators supporting each outcome. This can be a 1-5 or 1-7 Likert scale gauging roughly how many participants demonstrated indicators in a given outcome (e.g., almost none to most), or the overall perceived strength of the indicators (e.g., emerging to extensive).

The important thing with a scale is to be clear about what constitutes a certain rating. In the example below, it would be important to include a key that defines what “weak” looks like vs what “strong” looks like. This ensures that anyone filling out this form can appropriately gauge what’s happening in their program relative to others.

Below you can see what it looks like to have all the pieces put together. Of course, you should format yours in a way that makes sense for you.

7. Reflection questions

Finally, a reflection tool should include guiding questions around ideas you want to try for next time to prompt you to pay attention to any surprises and/or any trends you’re noticing, like if any particular outcomes or indicators are especially strong or could use more support. Some examples include:

Was there anything surprising that happened during the program? How so?

Looking over your notes as a whole, where do you notice participants are excelling? Are there any indicator groups that need improvement/greater emphasis in the future?

Is there anything you’d like to try differently next time based on your experiences during this program?

Which of the intended outcomes seems particularly challenging for your students? What additional supports might be helpful?

Think back to your initial goals for your participants. Do you feel participating in the program has supported students in achieving these goals? Why/why not?

While the process of completing the tool is an important part of the work, analyzing your data is the key to improving your practice. Soon, you may have a whole group of these reflective notes, constituting a rich data set to analyze alongside each other. You could compare the quantitative strength of the indicators over time; you might analyze trends in specific outcomes compared to others. You might collect all the ideas you documented about things to try in future programs and start a check list. How you use the data is up to you, and depends on what you’re curious to know about your program and participants.